This post is part 2 in a 3-part series. Please check out part 1 and part 3 as well.

We’ve seen the litany of moral failure from tech company executives: paying off tens of millions of dollars to executives accused of sexual harrassment (while sending victims away with nothing); firing women directly after they’ve had cancer treaments, major surgeries, or stillbirths; being told they were contributing to genocide and not responding to mitigate this; allowing top executives to evade responsibility and make deeply misleading statements in the New York Times; and more. Clearly, these executives are not going to lead us in AI ethics, when they are failing at “regular” ethics. The people who created our current problems will not be the ones to solve them, and it is up to the rest of us to act. In this series, I want to share actions you can take to have a practical, positive impact, and to highlight some real world examples. Some are big; some are small; not all of them will be relevant to your situation. Today’s post covers items 6-11 (see part 1 for 1-5 and part 3 for 12-16).

- Checklist for data projects

- Conduct ethical risks sweeps

- Resist the tyranny of metrics

- Choose a revenue model other than advertising

- Have product & engineering sit with trust & safety

- Advocate within your company

- Organize with other employees

- Leave your company when internal advocacy no longer works

- Avoid non-disparagement agreements

- Support thoughtful regulations & legislation

- Speak with reporters

- Decide in advance what your personal values and limits are

- Ask your company to sign the SafeFace Pledge

- Increase diversity by ensuring that employees from underrepresented groups are set up for success

- Increase diversity by overhauling your interviewing and onboarding processes

- Share your success stories!

Advocate within your company

Liz Fong-Jones was an engineer at Google for 11 years and remains a leader in the field of site reliability engineering. In a post about her recent decision to leave Google, she shares some of the strategies she used over the years to advocate for change from within the company. For instance, when Google announced in 2010 a real-name policy for Google+, which would be harmful for some teachers, therapists, LGBT+ people, and other vulnerable people, Liz put together a list of ways that the policy was misguided and could encourage abuse. Many of her colleagues joined her, and a group of employees was successful in gaining a seat at the negotiating table. In response to negative public feedback about the real-name policy, Google executives sought increased feedback from these employees and later removed the policy.

Employee Organizing (both internally and externally)

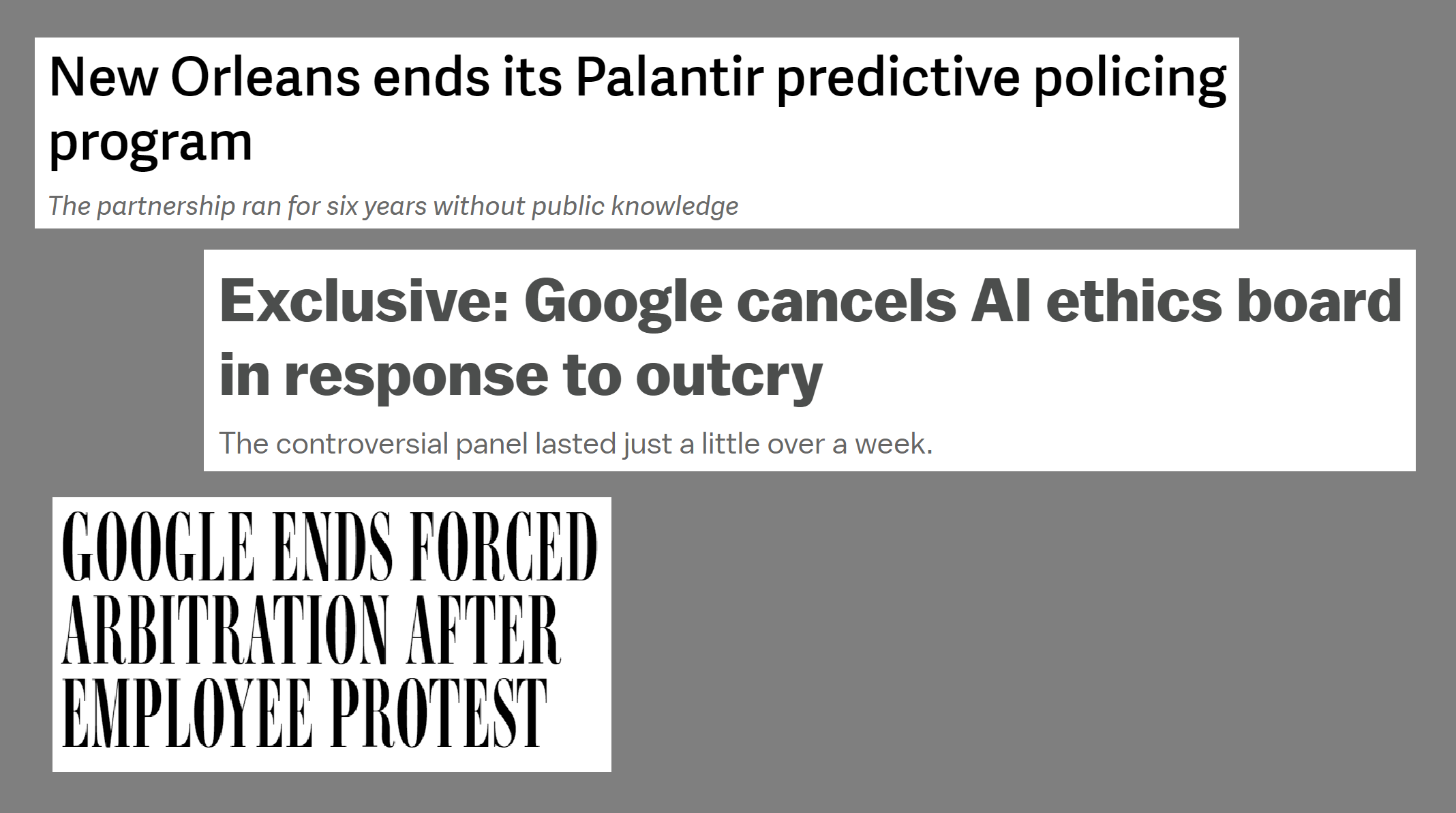

Much of the work Liz did falls under the category of employee organizing. Labor movements are most effective when they have clear goals and overarching principles, as opposed to simply being reactionary. There have been numerous recent employee movements and protests which have been successful: - Last year, Survey Monkey began offering full benefits to contract workers, in response to pressure from it’s full-time employees (contract workers are often treated like a lower caste by tech companies). - Google ended forced arbitration (which often prevents victims of sexual harassment or discrimination from seeking justice) after 20,000 employees participated in a protest of how the company has mishandled harassment cases and supported abusers. (See below for a note about how Google is now retaliating against the organizers). - After Google appointed the anti-trans, anti-LGBTQ, and anti-immigrant president of the Heritage Foundation to it’s AI Ethics board, over 2,000 Google employees signed a petition calling for her removal. Google ended up canceling the entire board, less than a week after they’d first announced it.

Just this week, news broke that Google has retaliated against the organizers of the Google Walkout, telling organizer Meredith Whittaker that she would have to “abandon” her work on AI ethics and her role at the AI Now Institute (which she co-founded), and another organizer, Claire Stapleton, received a demotion, lost half her reports, and was told to go on sick leave even though she isn’t sick. This is a common strategy by companies to attempt to intimidate employees in order to discourage them from organizing (and it highlights that companies do see such collective organizing as a threat). It is important that we show support and solidarity for organizing employees.

Leave your company when internal advocacy no longer works

Liz Fong-Jones writes that such tactics have proved less effective at Google more recently, and that she has been deeply troubled by the direction Google is heading in, with the harassment and doxxing of LGBT+ employees to white supremacist sites, putting profits above ethics in its business in China and the Middle East, and the huge financial payouts given to executives accused of sexually harassed subordinates. “I can no longer bail out a raft with a teaspoon while those steering punch holes in it,” Liz wrote about her decision to leave Google after 11 years.

Another tech industry employee who has followed this approach is Mark Luckie. Black users are one of the most engaged demographics on Facebook, yet Facebook often unjustly removes their content or wrongly suspends their accounts. Mark advocated for Black users and Black employees during his time working at Facebook, and eventually published a post Facebook is failing its black employees and its black users when he left.

For parents who are supporting children, non-US residents who are reliant on work visas, people with chronic health conditions, and many others, quitting a job without another one lined up is often not an option. Don’t worry, nobody is requiring that you do that. In the tech industry, a large number of companies are hiring and there is almost no stigma for switching jobs. As I wrote in a previous post about toxic jobs, people in the tech industry consistently underestimate their employability, how in-demand their skills are, and how many options they have.

Avoid non-disparagement agreements (if needed and when possible)

When the DataCamp CEO was accused of sexually assaulting one of his employees, the only repercussion for the assailant was a single day of sensitivity training (for more background on this, please read the posts by Noam Ross and Julia Silge on how instructors spent months collectively organizing for increased accountability and transparency, but DataCamp failed to engage in good faith). DataCamp employees Dhavide Aruliah and Greg Wilson brought up concerns internally about the mishandling of this case and how it set a precedent that executives could do what they want with impunity. Both Dhavide and Greg were fired within days of raising their concerns. They were offered severance packages which would have required them to sign agreements silencing them about what happened. Both declined this severance pay, which is what makes it possible now for them to speak out publicly (especially as DataCamp continues to handle the case poorly, by failing to engage with concerned DataCamp instructors, and by writing a victim-blaming “apology” with settings so that search engines won’t index it).

I appreciate all the DataCamp instructors who are organizing and calling for boycotts of their own courses, and I admire Dhavide and Greg for turning down a month’s salary so that they could continue to speak up. Please read their posts here and here. Not everyone can afford to turn down a severance package. That’s okay– not every item on this list applies to every situation, so do what you need to take care of yourself. However, if you can afford it, this can be a powerful tool.

Speak with reporters

Last year, the Verge reported on a secret program in New Orleans where Palantir had been testing out it’s predictive policing technology for the previous 6 years. The program was so secretive that even city council members weren’t aware of it prior to the article. There was a public outcry in response to the Verge’s article, and two weeks later, New Orleans chose not to renew its contract with Palantir. This is a win! I’m grateful to the reporters at the Verge who investigated this, and to the sources who bravely tipped off them off and spoke out about this (including one anonymous law enforcement official). Speaking to a journalist about your employer can be scary, but it can also be an effective strategy for enacting change.

I’m also grateful to the 20 current and former YouTube employees who spoke to reporters about the failure of YouTube (part of Google) leadership to act on toxic, extremist, & false videos, even as numerous employees raised alarms. I hope that you are financially supporting high quality journalism (through paid subscriptions or donations, depending on the outlet) if it is within your means to do so.

Support Thoughtful Regulations & Legislation

For years, I’ve had others in the tech industry look at me with shock and disgust when I say that I support thoughtful regulation. Well-enforced regulations are crucial and necessary to protect human rights and to ensure the well-being of society. Furthermore, regulations can even encourage innovation by ensuring stability and fair competition.

I’m so grateful for all the regulations that make our lives better in the USA, including the FDA, EPA, Civil Rights Act, Fair Housing Act, Pregnancy Discrimination Act, Americans with Disabilities Act, Age Discrimination in Employment Act, National Research Act, Family Medical Leave Act, and Freedom of Information Act. The Voting Rights Act was crucial, and I’m angry that it was gutted in 2013. I’m grateful that California passed a stricter vaccination law in 2015. I’m grateful for car safety standards. These laws did not occcur in a vaccum, and I am grateful to the activists and advocates that worked for years (and in many cases, decades) to get these regulations passed.

The regulations and acts I listed above could all be improved. Some of them are not enforced well enough, and some are currently under attack. Some of them don’t go far enough. My point is not that they are perfect; my point is that regulations can be good and helpful. Yes, there are plenty of regulations that are stupid or harmful, but I talk to far too many people in the tech industry who have concluded that ALL regulations are bad or destined to fail.

Getting thoughtful regulation passed will be challenging, but we need to protect human rights, and to counterbalance the huge power that corporations currently have. We also need to be skeptical of how corporate leaders often say one thing while the lobbyists they employ work towards the opposite. The tech giants are currently earning a ton of money (while externalizing many costs to society) and we can not underestimate how hard they will fight against meaningful changes that would impact their profits.

If you want to know where tech companies stand on an issue, look at the actions of their lobbyists, not the statements from their leaders. https://t.co/o7TZtMDAjU

— Rachel Thomas (@math_rachel) April 17, 2019

To be continued…

This post is the second in a series. You can find part 1 here and part 3 here. The problems we are facing can be overwhelming, so it may help to choose a single item from this list as a good way to start. I encourage you to choose one thing you will do, and to make a commitment now.

Other fast.ai posts on tech ethics

- Was this Google Executive deeply misinformed or lying in the New York Times?

- Five Things That Scare Me About AI

- AI Ethics Resources

- What HBR Gets Wrong About Algorithms and Bias

- What you need to know about Facebook and Ethics

- A Conversation about Tech Ethics with the New York Times Chief Data Scientist