YouTube has played a significant role in radicalizing people into conspiracy theories that promote white supremacy, anti-vaxxing, denial of mass shootings, climate change denial, and distrust of mainstream media, by aggressively recommending (and autoplaying) videos on these topics to people who weren’t even looking for them. YouTube recommendations account for 70% of time spent on the platform, and these recommendations disproportionately include harmful conspiracy theories. YouTube’s recommendation algorithm is trying to maximize watch time, and content that convinces you the rest of the media is lying will result in more time spent watching YouTube.

Given all this, you might expect that Google/YouTube takes these issues seriously and is working to address them. However, when the New York Times interviewed YouTube’s most senior product executive, Neal Mohan, he made a series of statements that, in my opinion, were highly misleading, perpetuated misconceptions, denied responsibility, and minimized an issue that has destroyed lives. Mohan has been a senior executive at Google for over 10 years and has 20 years of experience in the internet ad industry (which is Google/YouTube’s core business model). Google is well-known for carefully controlling its public image, yet Google has not issued any sort of retraction or correction of Mohan’s statements. Between Mohan’s expertise and Google’s control over its image, we can’t just dismiss this interview.

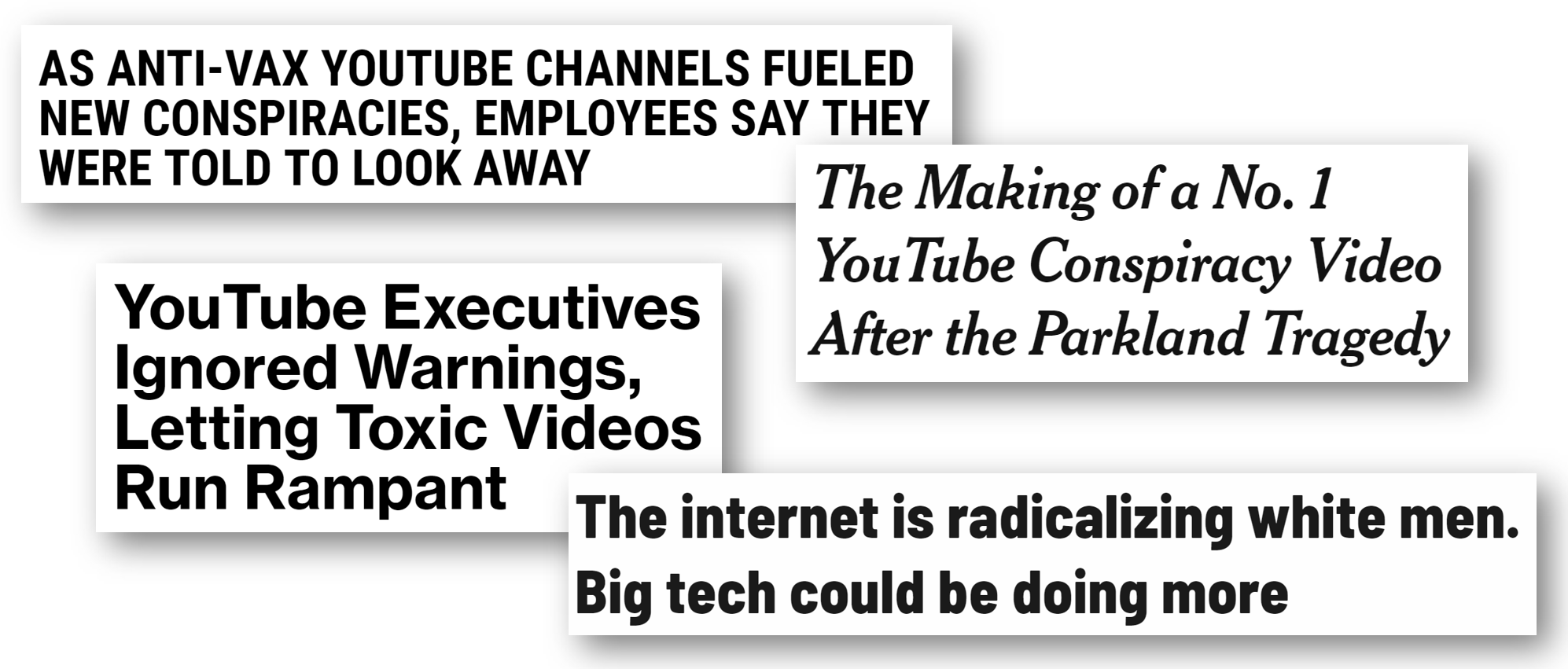

Radicalization via YouTube

Worldwide, people watch 1 billion hours of YouTube per day (yes, that says PER DAY). A large part of YouTube’s successs has been due to its recommendation system, in which a panel of recommended videos are shown to the user and the top video automatically begin playing once the previous video is over. This drives 70% of time spent on YouTube. Unfortunately, these recommendations are disproportionately for conspiracy theories promoting white supremacy, anti-vaxxing, denial of mass shootings, climate change denial, and denying the accuracy of mainstream media sources. “YouTube may be one of the most powerful radicalizing instruments of the 21st century,” Professor Zeynep Tufekci wrote in the New York Times. YouTube is owned by Google, which is earning billions of dollars by aggressively introducing vulnerable people to conspiracy theories, while the rest of society bears the externalized costs.

The number of people telling me that YouTube autoplay ends up with white supremacists videos from all sorts of starting points is pretty staggering. This needs large-scale and systematic research. https://t.co/NnTdQA9itK

— zeynep tufekci (@zeynep) March 12, 2018

What is going on? YouTube’s algorithm was built to maximize how much time people spend watching YouTube, and conspiracy theorists watch significantly more YouTube than people who trust a variety of media sources. Unfortunately, a recommendation system trying only to maximize time spent on its own platform will incentivize content that tells you the rest of the media is lying, as explained by YouTube whistleblower Guillaume Chaslot.

What research has been done on this?

Guillaume Chaslot, who has a PhD in artificial intelligence and previously worked at Google on YouTube’s recommendation system, wrote software which does a YouTube search with a “seed” phrase (such as “Donald Trump”, “Michelle Obama”, or “is the earth round or flat?”), and records what video is “Up Next” as the top recommendation, and then follows what video is “Up Next” next after that, and so on. The software does this with no viewing history (so that the recommendations are not influenced by user preferences), and repeats this thousands of times.

Chaslot collected 8,000 videos from “Up Next” recommendations between August-November 2016: half came as part of the chain of recommendations after searching for “Clinton” and half after searching for “Trump”. When Guardian reporters analyzed the videos, they found that they were 6 times as likely to be anti-Hillary Clinton (regardless of whether the user had searched for “Trump” or “Clinton”), and that many contained wild conspiracy theories:

“There were dozens of clips stating Clinton had had a mental breakdown, reporting she had syphilis or Parkinson’s disease, accusing her of having secret sexual relationships, including with Yoko Ono. Many were even darker, fabricating the contents of WikiLeaks disclosures to make unfounded claims, accusing Clinton of involvement in murders or connecting her to satanic and paedophilic cults.”

This is just one of many themes that Chaslot has researched. Chaslot’s quantitative research on YouTube’s recommendations has been covered by The Wall Street Journal, NBC, MIT Tech Review, The Washington Post, Wired, and elsewhere.

In Feb 2018, Google Promised to Publish a Blog Post Refuting Chaslot (but still hasn’t)

According to the Columbia Journalism Review, “When The Guardian wrote about Chaslot’s research, he says representatives from Google and YouTube criticized his methodology and tried to convince the news outlet not to do the story, and promising to publish a blog post refuting his claims. No such post was ever published. Google said it ‘strongly disagreed’ with the research—but after Senator Mark Warner raised concerns about YouTube promoting what he called ‘outrageous, salacious, and often fraudulent content,’ Google thanked The Guardian for doing the story.” (emphasis mine)

Why would Google claim that they had evidence refuting Chaslot’s research, and then never publish it? The Guardian story ran over a year ago, yet Google has still not produced their promised blog post. This suggests to me that Google was lying. It is important to keep this in mind when weighing the truthfulness of more recent claims by Google leaders regarding YouTube.

What did Neal Mohan get wrong?

YouTube’s Chief Product Officer, Neal Mohan, was interviewed in the New York Times, where he seemed to deny a well-documented phenomenon, ignored that 70% of time spent on the site comes from autoplaying recommendations (instead blaming users for what videos they choose to click on), made a nonsensical “both sides” argument (even though YouTube has extremist videos, they also have non-extremist videos…?), and perpetuated misconceptions (suggesting that since extremism isn’t an explicit input to the algorithm, that the results can’t be biased towards extremism). In general, his answers often seemed evasive, failing to answer the question that had been asked, and at no point did he seem to take responsibility for any mistakes or harms caused by YouTube.

Even the reporter interviewing Mohan seemed surprised, at one point interrrupting him to clarify, “Sorry, can I just interrupt you there for a second? Just let me be clear: You’re saying that there is no rabbit hole effect on YouTube?” (The “rabbit hole effect” is when the recommendation system gradually recommends videos that are more and more extreme). In response, Mohan blamed users and still failed to give a straightforward answer.

As background, Mohan first began working in the internet ad industry in 1997 at DoubleClick, which was aquired by Google for $3.1 billion in 2008. Mohan then served as SVP of display and video ads for Google for 7 years, before switching into the role of Chief Product Officer for Google’s YouTube. YouTube’s primary source of revenue is ads, and in 2018, YouTube was estimated to be doing $15 billion in annual sales and to be worth as much as $100 billion. Mohan is so beloved by Google that they offered him an additional $100 million in stock in 2013 to turn down a job offer from Twitter. All in all, this means that Mohan has 11 years of experience as a Google senior executive, and over 20 years of experience in the internet ad industry.

All the data, evidence, & research shows that extremism drives engagement and that YouTube promotes extremism.

“It is not the case that ‘extreme’ content drives a higher version of engagement or watch time than content of other types.” –Neal Mohan

Unfortunately, any recommendation system trying only to maximize time spent on its own platform will incentivize content that tells you the rest of the media is lying. A 2012 Google blog post and a 2016 paper published by YouTube engineers both confirm this: the YouTube algorithm was designed to maximize watch time. Ex-YouTube engineer Guillaume Chaslot explains the dynamic in more detail here.

The issues of YouTube’s role in radicalization has been confirmed by investigations by the Wall Street Journal and the Guardian, quantitative research projects such as AlgoTransparency, and by 20 current and former YouTube employees. Five senior personnel who quit Google/YouTube in the last 2 years privately cited the failure of YouTube’s leadership to address false, incendiary, and toxic content as their reason for leaving. That Mohan would try to deny this seems as outlandish as many of the conspiracy theories promoted on YouTube.

If @YouTube or @nealmohan have data supporting this claim (that extreme content does not drive higher engagement), they absolutely should release it, since it contradicts all existing research & data on this topic. pic.twitter.com/8Sr6eDHgZG

— Rachel Thomas (@math_rachel) March 30, 2019

According to a Bloomberg investigation, Google leaders have repeatedly rejected efforts of YouTube staff who sought to address or even just investigate the issue of false, incendiary, & toxic content “One employee wanted to flag troubling videos, which fell just short of the hate speech rules, and stop recommending them to viewers. Another wanted to track these videos in a spreadsheet to chart their popularity. A third, fretful of the spread of “alt-right” video bloggers, created an internal vertical that showed just how popular they were. Each time they got the same basic response: Don’t rock the boat… In February of 2018, a video calling the Parkland shooting victims “crisis actors” went viral on YouTube’s trending page. Policy staff suggested soon after limiting recommendations on the page to vetted news sources. YouTube management rejected the proposal.”

70% of YouTube views come from autoplaying its recommendations

“I’m not saying that a user couldn’t click on one of those videos that are quote-unquote more extreme, consume that and then get another set of recommendations and sort of keep moving in one path or the other. All I’m saying is that it’s not inevitable.” –Neal Mohan

This statement ignores the way that YouTube’s autoplay works in conjunction with recommendations, which drives 70% of time that users spend on the site, according to a previous talk Neal Mohan gave. Yes, technically, it is not “inevitable”, but it is the mechanism driving 700 million hours of watched videos PER DAY (70% of 1 billion). Mohan’s statement suggests that users are choosing to click on extreme videos, whereas in most cases, videos are being selected by YouTube and automaticaly begin playing without any clicking required.

Case study: Alex Jones

To understand the role of YouTube’s autoplaying recommendations, it is crucial to understand the distinction between hosting content and promoting content. To illustrate with an example, YouTube recommended Infowars director Alex Jones 15,000,000,000 times (before banning him in August 2018). If you are not familiar with Alex Jones, the Southern Poverty Law Center rates him as the most prolific conspiracy theorist of contemporary times. One of his conspiracy theories is that the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, in which 20 children were murdered, was faked, and that the parents of the murdered children are lying. This has resulted in a years long harassment campaign against these grieving parents– many of them have had to move multiple times to try to evade harassment and one father recently committed suicide. Alex Jones also advocates for white supremacy, against vaccines, and that victims of the Parkland school shooting are “crisis actors”.

The algorithm I worked on at Google recommended Alex Jones' videos more than 15,000,000,000 times, to some of the most vulnerable people in the nation.

— Guillaume Chaslot (@gchaslot) February 25, 2018

The issue is not that people were searching for Alex Jones videos; the issue is that YouTube recommended (and often began autoplaying) Alex Jones videos 15,000,000,000 times to people who weren’t even looking for them. More recently, YouTube has been aggressively promoting content from Russia Today (RT), a Russian state-owned propaganda outlet.

As computational propaganda expert Renee DiResta wrote for Wired, “There is no First Amendment right to amplification—and the algorithm is already deciding what you see. Content-based recommendation systems and collaborative filtering are never neutral; they are always ranking one video, pin, or group against another when they’re deciding what to show you.” Autoplaying conspiracy theories boosts YouTube’s revenue– as people are radicalized, they stop spending time on mainstream media outlets and spend more and more time on YouTube.

Algorithms can be biased on variables that aren’t part of the dataset.

“What I’m saying is that when a video is watched, you will see a number of videos that are then recommended. Some of those videos might have the perception of skewing in one direction or, you know, call it more extreme. There are other videos that skew in the opposite direction,” Mohan gave a vague “both sides” defense, although it is unclear how less extreme videos balance out more extreme videos. He continued, “And again, our systems are not doing this, because that’s not a signal that feeds into the recommendations.” Mohan is suggesting that since extremism is not an explicit variable that is fed into the algorithm, the algorithm can’t be biased towards extremist material. This is false, but a common and dangerous misconception.

Algorithms can be (and often are) biased on variables that are not a part of the dataset. In fact, this is what machine learning does: it picks out latent variables. For example, the COMPAS recidivism algorithm, used in many USA courtrooms as part of bail, sentencing, or parole decisions, was found to have nearly twice as high a false positive rate for Black defendents compared to white defendents. That is, 45% of Black defendents who were labeled as “high-risk” did not commit another crime; compared to 24% of white defendents. Race is not an input variable to this software, so by Mohan’s reasoning, there should be no problem.

Reminder: algorithms can be biased on variables that are not a part of the dataset.

— Rachel Thomas (@math_rachel) March 30, 2019

Ex: Race is not an input variable to COMPAS recidivism algorithm, yet the results are racially biased.

YouTube doesn't use extremism as a variable, but its results are biased towards extremism.

Not only does ignoring factors like race, gender, or extremism not protect you from biased results, many machine learning experts recommend the opposite: you need to be measuring these quantities to ensure that you are not unjustly biased.

Like many people around the world, I’m alarmed by the resurgence in white supremacist movements and continued denialism of climate change, and it sickens me to think how much money YouTube has earned by aggressively promoting such conspiracy theories to people who weren’t even looking for them. I spend most of my time studying AI ethics, and I have been including YouTube’s behavior as an example (of what not to do) in my keynote talks for the last 2 years. Even though I know the big tech companies won’t do the right thing unless forced to by meaningful regulation, I was still disheartened by this New York Times interview. Not only does Google/YouTube still not take these issues seriously, but it is insulting that they think the rest of us will be placated by their misleading corporate-speak and half-baked evasions.